First, new FOMC member Neil Kashkari tells us why he dissented on this week's interest rate hike. It's a great essay. I laughed at "over the past five years, 100 percent of the medium-term inflation forecasts (midpoints) in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections have been too high: We keep predicting that inflation is around the corner." That's some 20 forecasts all missed in the same direction. Impressive.

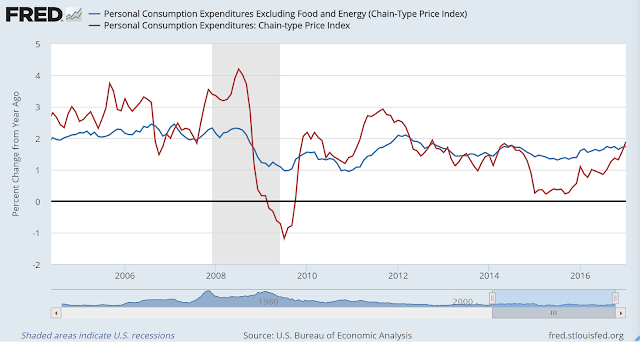

This is exactly the problem with monetary policy in the US, Europe, and Japan. Central banks keep predicting that inflation will return to target. When it doesn't, however, they don't respond by loosening policy, or by updating their inflation forecasts. They just continue being predictably wrong. He makes a number of good points, including that the Fed shouldn't treat their target as though the risks are asymmetric, like they are driving near a cliff. They should occasionally miss by going over 2%. If anything, the worry should be that if the US had a negative shock again, the Fed would have more trouble managing the economy at the zero lower bound. The asymmetric risk is an economy growing too slowly. What he doesn't mention is that this logic should imply a higher inflation target -- but I'll give him a pass on this. Yet another good point he makes is that the rest of the developed world is currently suffering from very low inflation. How likely is it that the US will soon suffer from an inflation spiral that can't be controlled by repeated interest rate increases? When other developed countries have inflation close to zero? Core inflation in the US is just 1.74, he notes, up from 1.71% last year. We appear to be some ways away from an inflation spiral.

Another thing he doesn't do is discuss the fact that, not only has the Fed repeatedly missed its inflation forecasts in the past few years, but it has also under-performed its GDP growth forecasts. You'd think, if you wanted to drive down the center of the road, when you notice your car heading off onto the shoulder that you'd adjust the steering wheel back toward the center. The Fed instead has repeatedly decided not to do this, and then been surprised that the car doesn't return to the center of the road by itself. Many academics then argue that maybe it's because the steering wheel doesn't work. I say the problem isn't with the steering wheel, but that the driver refuses to adjust.

Thus I want to flag another short article, on Japan, which argues exactly this. Sayuri Shirai writes that Japan's non-standard monetary policies since it reached the zero lower bound have not been effective, and argues that Japan should thus raise interest rates. One tell that the author is overselling the ineffectiveness of MP at the ZLB is that although she credits Japan's MP easing with weakening the Yen after 2013, she writes "the yen’s depreciation has reduced the prices of exports but increased those of imports so that the net positive impact has not been as large as in the more distant past." How could a Yen devaluation simultaneously reduce the price of exports and increase import prices? Presumably, many of Japan's exports to the US, for example, are actually priced in dollars. In Yen terms, these prices are thus likely to rise substantially with a fall in the value of the Yen. The article doesn't back up these claims.

The author also doesn't back up other claims, such as that the negative interest rate policy supposedly caused a rash of bad effects, such as "a deterioration in households’ sentiments" and "potential financial instability risk". If either of these were the case, it could easily be documented using high-frequency data from surprise announcements. But that isn't what people who look at the impact of MP announcements at the ZLB typically find. Interestingly, although much of the article is about the negative interest rates, the author never mentions that Japanese rates are just -.1%. Color me skeptical that a change of just .1% is really going to have these dramatic negative effects proposed in the article. Keep in mind that back before the ZLB episode, the BOJ once raised interest rates 3.5% in one year to fight inflation, and in the 1970s, they cut interest rates as much as 6% in a loosening cycle over 2-3 years to fight a recession. That's 60 times more medicine than a move from 0 to -.1%. To provide a similar amount of ammunition now, of course an enormous balance sheet expansion would be in order. It's clearly foolish to conclude that since things haven't gone better since Japan cut interest rates from 0 to -.1%, that Japan should now raise rates.

Aside from the fact that announcements have tended to move things in the right direction for Japan, the author also misses that many times, even as new data comes in which is below the BOJ's forecast, they've declined to take on more stimulative policies, occasionally disappointing markets and tightening monetary conditions. It's hard not to watch this and conclude that the Bank is not totally committed to its growth and inflation targets. A good analogy is your friend who states he wants to lose weight, but refuses to go to the gym more than once a month. Since going to the gym once a month isn't working, why go at all? That's what Shirai is telling us.

This is exactly the problem with monetary policy in the US, Europe, and Japan. Central banks keep predicting that inflation will return to target. When it doesn't, however, they don't respond by loosening policy, or by updating their inflation forecasts. They just continue being predictably wrong. He makes a number of good points, including that the Fed shouldn't treat their target as though the risks are asymmetric, like they are driving near a cliff. They should occasionally miss by going over 2%. If anything, the worry should be that if the US had a negative shock again, the Fed would have more trouble managing the economy at the zero lower bound. The asymmetric risk is an economy growing too slowly. What he doesn't mention is that this logic should imply a higher inflation target -- but I'll give him a pass on this. Yet another good point he makes is that the rest of the developed world is currently suffering from very low inflation. How likely is it that the US will soon suffer from an inflation spiral that can't be controlled by repeated interest rate increases? When other developed countries have inflation close to zero? Core inflation in the US is just 1.74, he notes, up from 1.71% last year. We appear to be some ways away from an inflation spiral.

Another thing he doesn't do is discuss the fact that, not only has the Fed repeatedly missed its inflation forecasts in the past few years, but it has also under-performed its GDP growth forecasts. You'd think, if you wanted to drive down the center of the road, when you notice your car heading off onto the shoulder that you'd adjust the steering wheel back toward the center. The Fed instead has repeatedly decided not to do this, and then been surprised that the car doesn't return to the center of the road by itself. Many academics then argue that maybe it's because the steering wheel doesn't work. I say the problem isn't with the steering wheel, but that the driver refuses to adjust.

Thus I want to flag another short article, on Japan, which argues exactly this. Sayuri Shirai writes that Japan's non-standard monetary policies since it reached the zero lower bound have not been effective, and argues that Japan should thus raise interest rates. One tell that the author is overselling the ineffectiveness of MP at the ZLB is that although she credits Japan's MP easing with weakening the Yen after 2013, she writes "the yen’s depreciation has reduced the prices of exports but increased those of imports so that the net positive impact has not been as large as in the more distant past." How could a Yen devaluation simultaneously reduce the price of exports and increase import prices? Presumably, many of Japan's exports to the US, for example, are actually priced in dollars. In Yen terms, these prices are thus likely to rise substantially with a fall in the value of the Yen. The article doesn't back up these claims.

The author also doesn't back up other claims, such as that the negative interest rate policy supposedly caused a rash of bad effects, such as "a deterioration in households’ sentiments" and "potential financial instability risk". If either of these were the case, it could easily be documented using high-frequency data from surprise announcements. But that isn't what people who look at the impact of MP announcements at the ZLB typically find. Interestingly, although much of the article is about the negative interest rates, the author never mentions that Japanese rates are just -.1%. Color me skeptical that a change of just .1% is really going to have these dramatic negative effects proposed in the article. Keep in mind that back before the ZLB episode, the BOJ once raised interest rates 3.5% in one year to fight inflation, and in the 1970s, they cut interest rates as much as 6% in a loosening cycle over 2-3 years to fight a recession. That's 60 times more medicine than a move from 0 to -.1%. To provide a similar amount of ammunition now, of course an enormous balance sheet expansion would be in order. It's clearly foolish to conclude that since things haven't gone better since Japan cut interest rates from 0 to -.1%, that Japan should now raise rates.

Aside from the fact that announcements have tended to move things in the right direction for Japan, the author also misses that many times, even as new data comes in which is below the BOJ's forecast, they've declined to take on more stimulative policies, occasionally disappointing markets and tightening monetary conditions. It's hard not to watch this and conclude that the Bank is not totally committed to its growth and inflation targets. A good analogy is your friend who states he wants to lose weight, but refuses to go to the gym more than once a month. Since going to the gym once a month isn't working, why go at all? That's what Shirai is telling us.