On January 22, 2013, the Government and the Bank of Japan issued a rare joint statement on overcoming deflation and achieving sustainable economic growth. The purpose of the statement was to introduce a two percent inflation target. It was issued jointly to emphasize that the monetary and fiscal authorities could be expected to coordinate for the purpose of achieving their shared goal--a clear attempt to enhance the credibility of the new inflation target.

On April 4, 2013, the BOJ explained how it intended to achieve the inflation target: Quantitative and Qualitative Easing. QQE is (more or less) standard monetary policy, except on a larger than normal scale. That is, the policy entails the creation of bank reserves (money) which are then used to purchase securities--primarily government bonds (JGBs).

At the time, I was skeptical that the policy would work as intended (see here). My skepticism has not abated since then. This post is about explaining why. In a nutshell, my argument is that while the BOJ seems willing to increase inflation, it is largely unable to--and while the government is able to increase inflation, it seems unwilling to. In short, the necessary policy coordination appears to be absent.

Let's begin with some basics. First, note that a JGB is basically an interest-bearing claim to (possibly) interest-bearing BOJ money. The total nominal government debt is the sum of BOJ money and JGBs. The fiscal authority controls the total supply of debt. The monetary authority determines its composition (between money and bonds). Quantitative easing increases the supply of money and reduces the supply of bonds held in the wealth portfolios of private agents. That is, it changes the composition of government debt without changing its level.

Because bonds are normally discounted (that is, they generally earn a higher yield than money), an open-market operation that alters the composition of government debt will generally have real and nominal consequences. But in present circumstances, the yield and risk characteristics of Japanese money and bonds are very similar. In the limiting case where money and bonds are perfect substitutes (we're not quite there yet), altering the composition of government debt (without affecting its level) is inconsequential. It's like swapping one hundred dollars in $10 bills for one hundred $1 bills. Such an operation--even it is permanent--is not likely to have any measurable effect on the economy, including the price-level. Why should it? Empirically, it didn't seem to have any measurable impact on inflation the first time Japan tried QE from 2002-2006 (see also my 2003 paper here, section VI).

For the rate of inflation to rise, one of two things must happen: [1] the growth rate in the supply of nominal government debt must rise; or [2] the growth rate in the demand for government debt must fall.

One interpretation of what has happened in Japan (and elsewhere) is that a persistently bearish sentiment has led to an elevated growth in the demand for safe securities, like JGBs (at the expense of private investment). The effect of this force is to drive down bond yields and create deflationary pressure (deflation is a market mechanism for increasing the growth rate of the real quantity of nominal object when it is in short supply.) While the supply of nominal debt has been rising, ultra-low bond yields and lowflation suggest that the demand for debt has been rising even more rapidly.

According to the joint statement mentioned above, the government's commitment to helping the BOJ achieve the 2% inflation target amounts to reducing the demand for government debt by implementing reforms intended to create a bullish investment climate designed to stimulate real economic growth (the third of Abe's three arrows). While this is fine as far as it goes, what's the contingency plan in case the third arrow cannot be released or misses its mark?

In my view, the appropriate contingency plan would involve a promise to use nominal debt to finance (say) social security payments or tax cuts as long as inflation remains below target. This is essentially "helicopter money." The "money" in this case is government debt (whether the BOJ monetizes new debt or not is irrelevant if the two objects are perfect substitutes). Importantly (and as far as I understand), the BOJ has no authority to engage in helicopter money. Only the government can do this. And in present circumstances, my view is that only a commitment on the part of the government to adjust money/debt-finance expenditures to meet the inflation target can render it credible. The question is whether the government has expressed any willingness to support the inflation target in this manner. All the evidence I can find suggests that the answer is no.

To begin, the Japanese government appears to be very concerned with the size (and growth) of its public debt. From the joint statement above:

The government of Japan, however, appears almost obsessively concerned with deficit reduction. Publications from the Ministry of Finance seem to go out of their way in raising debt-sustainability alarm bells. Consider the contents of this Japanese Public Finance Fact Sheet, for example. Most of the document stresses the need for "fiscal consolidation" (deficit reduction) and includes lessons to be drawn from the European debt crisis. The graph of total government expenditure on page 4 strangely includes spending on the repayment of debt. And on page 3, there is the familiar and misleading "here is what a family's balance sheet would look like if it behaved like the government" exercise. This is a great way to promote the government's seriousness about stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio. But it is not, in my view, a policy that is consistent with helping the BOJ achieve its 2% inflation target.

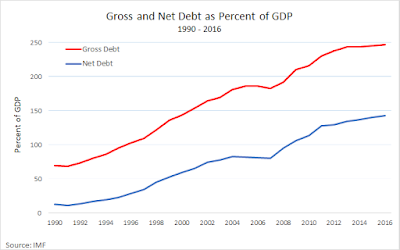

And by the way, just how serious is the government debt problem in Japan? Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio is presently 250%, or so we are told. As it turns out, this figure overstates the level of public debt (see here, section 3.1). The 250% figure represents gross debt, which includes government loans and certain intragovernmental transfers, all of which should be netted out. Once this is done, the net debt-to-GDP ratio is closer to 150%.

Moreover, if one further accounts for the sizable quantity of government assets, the ratio falls to 100% (see the balance sheet of the central government here on page 51). And finally, if one was to view the fact that 40% of government bonds are held by the BOJ and likely to remain monetized, the ratio falls further still. In my view, the very low yield on JGB's reflects the market's assessment that public finances in Japan are nowhere near being out of order (a caveat to this view here).

So, relative to the market demand for their product, the government of Japan appears to be in "austerity" mode--it is bent on limiting the supply of highly-valued JGBs. In the meantime, the BOJ is aggressively purchasing the limited supply of JGBs to the point where it is now worried that the supply of bonds available for purchase will soon be exhausted (story here).

How can the BOJ credibly promise to continue with its bond purchases until its inflation target is met? It can't. Not without the proper support from the government, which appears not to be coming anytime soon. And so, after a transitory blip in inflation following the austerity-induced VAT, headline CPI is back near zero territory.

Partly out of a concern over running out of eligible securities to purchase, the BOJ recently announced a new negative interest rate policy (NIRP) with yield curve control (YCC); see here. The intervention appears to have little impact on inflation expectations (inflation and inflation expectations today are similar to the early 2000s, prior to the financial crisis).

Let me conclude. First, this post is not meant as an argument in favor of the 2% inflation target. Second, it should not be construed as an argument against the Japanese government's debt management strategy. Nor is it an argument against the BOJ's asset purchase program. I will discuss these issues in a subsequent post.

The point of this post is as follows. IF the monetary and fiscal authorities wish to implement a 2% inflation target, THEN success of the policy (in present circumstances) requires a sufficiently accommodative fiscal policy (deficit financed expenditures and/or tax cuts) when inflation and inflation expectations are running below target. Absent this commitment on the part of the fiscal authority, the endeavor is ultimately doomed (if an overall bearish outlook persists) and--as a consequence--the credibility of a monetary authority that keeps promising an inflation it cannot deliver may at some point be jeopardized.

Additional readings:

[1] Understanding lowflation.

[2] A model of U.S. monetary policy before and after the great recession.

On April 4, 2013, the BOJ explained how it intended to achieve the inflation target: Quantitative and Qualitative Easing. QQE is (more or less) standard monetary policy, except on a larger than normal scale. That is, the policy entails the creation of bank reserves (money) which are then used to purchase securities--primarily government bonds (JGBs).

At the time, I was skeptical that the policy would work as intended (see here). My skepticism has not abated since then. This post is about explaining why. In a nutshell, my argument is that while the BOJ seems willing to increase inflation, it is largely unable to--and while the government is able to increase inflation, it seems unwilling to. In short, the necessary policy coordination appears to be absent.

Let's begin with some basics. First, note that a JGB is basically an interest-bearing claim to (possibly) interest-bearing BOJ money. The total nominal government debt is the sum of BOJ money and JGBs. The fiscal authority controls the total supply of debt. The monetary authority determines its composition (between money and bonds). Quantitative easing increases the supply of money and reduces the supply of bonds held in the wealth portfolios of private agents. That is, it changes the composition of government debt without changing its level.

Because bonds are normally discounted (that is, they generally earn a higher yield than money), an open-market operation that alters the composition of government debt will generally have real and nominal consequences. But in present circumstances, the yield and risk characteristics of Japanese money and bonds are very similar. In the limiting case where money and bonds are perfect substitutes (we're not quite there yet), altering the composition of government debt (without affecting its level) is inconsequential. It's like swapping one hundred dollars in $10 bills for one hundred $1 bills. Such an operation--even it is permanent--is not likely to have any measurable effect on the economy, including the price-level. Why should it? Empirically, it didn't seem to have any measurable impact on inflation the first time Japan tried QE from 2002-2006 (see also my 2003 paper here, section VI).

For the rate of inflation to rise, one of two things must happen: [1] the growth rate in the supply of nominal government debt must rise; or [2] the growth rate in the demand for government debt must fall.

One interpretation of what has happened in Japan (and elsewhere) is that a persistently bearish sentiment has led to an elevated growth in the demand for safe securities, like JGBs (at the expense of private investment). The effect of this force is to drive down bond yields and create deflationary pressure (deflation is a market mechanism for increasing the growth rate of the real quantity of nominal object when it is in short supply.) While the supply of nominal debt has been rising, ultra-low bond yields and lowflation suggest that the demand for debt has been rising even more rapidly.

According to the joint statement mentioned above, the government's commitment to helping the BOJ achieve the 2% inflation target amounts to reducing the demand for government debt by implementing reforms intended to create a bullish investment climate designed to stimulate real economic growth (the third of Abe's three arrows). While this is fine as far as it goes, what's the contingency plan in case the third arrow cannot be released or misses its mark?

In my view, the appropriate contingency plan would involve a promise to use nominal debt to finance (say) social security payments or tax cuts as long as inflation remains below target. This is essentially "helicopter money." The "money" in this case is government debt (whether the BOJ monetizes new debt or not is irrelevant if the two objects are perfect substitutes). Importantly (and as far as I understand), the BOJ has no authority to engage in helicopter money. Only the government can do this. And in present circumstances, my view is that only a commitment on the part of the government to adjust money/debt-finance expenditures to meet the inflation target can render it credible. The question is whether the government has expressed any willingness to support the inflation target in this manner. All the evidence I can find suggests that the answer is no.

To begin, the Japanese government appears to be very concerned with the size (and growth) of its public debt. From the joint statement above:

In addition, in strengthening coordination between the Government and the Bank of Japan, the Government will steadily promote measures aimed at establishing a sustainable fiscal structure with a view to ensuring the credibility of fiscal management.Now don't get me wrong--everyone agrees that a "sustainable fiscal structure" is a good thing. The question is in determining what is sustainable. Of course, the debt-to-GDP ratio cannot rise forever. But it may certainly rise to a much higher level, even from its current elevated position, especially in light of how low interest rates presently are.

The government of Japan, however, appears almost obsessively concerned with deficit reduction. Publications from the Ministry of Finance seem to go out of their way in raising debt-sustainability alarm bells. Consider the contents of this Japanese Public Finance Fact Sheet, for example. Most of the document stresses the need for "fiscal consolidation" (deficit reduction) and includes lessons to be drawn from the European debt crisis. The graph of total government expenditure on page 4 strangely includes spending on the repayment of debt. And on page 3, there is the familiar and misleading "here is what a family's balance sheet would look like if it behaved like the government" exercise. This is a great way to promote the government's seriousness about stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio. But it is not, in my view, a policy that is consistent with helping the BOJ achieve its 2% inflation target.

And by the way, just how serious is the government debt problem in Japan? Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio is presently 250%, or so we are told. As it turns out, this figure overstates the level of public debt (see here, section 3.1). The 250% figure represents gross debt, which includes government loans and certain intragovernmental transfers, all of which should be netted out. Once this is done, the net debt-to-GDP ratio is closer to 150%.

Moreover, if one further accounts for the sizable quantity of government assets, the ratio falls to 100% (see the balance sheet of the central government here on page 51). And finally, if one was to view the fact that 40% of government bonds are held by the BOJ and likely to remain monetized, the ratio falls further still. In my view, the very low yield on JGB's reflects the market's assessment that public finances in Japan are nowhere near being out of order (a caveat to this view here).

So, relative to the market demand for their product, the government of Japan appears to be in "austerity" mode--it is bent on limiting the supply of highly-valued JGBs. In the meantime, the BOJ is aggressively purchasing the limited supply of JGBs to the point where it is now worried that the supply of bonds available for purchase will soon be exhausted (story here).

How can the BOJ credibly promise to continue with its bond purchases until its inflation target is met? It can't. Not without the proper support from the government, which appears not to be coming anytime soon. And so, after a transitory blip in inflation following the austerity-induced VAT, headline CPI is back near zero territory.

Partly out of a concern over running out of eligible securities to purchase, the BOJ recently announced a new negative interest rate policy (NIRP) with yield curve control (YCC); see here. The intervention appears to have little impact on inflation expectations (inflation and inflation expectations today are similar to the early 2000s, prior to the financial crisis).

Let me conclude. First, this post is not meant as an argument in favor of the 2% inflation target. Second, it should not be construed as an argument against the Japanese government's debt management strategy. Nor is it an argument against the BOJ's asset purchase program. I will discuss these issues in a subsequent post.

The point of this post is as follows. IF the monetary and fiscal authorities wish to implement a 2% inflation target, THEN success of the policy (in present circumstances) requires a sufficiently accommodative fiscal policy (deficit financed expenditures and/or tax cuts) when inflation and inflation expectations are running below target. Absent this commitment on the part of the fiscal authority, the endeavor is ultimately doomed (if an overall bearish outlook persists) and--as a consequence--the credibility of a monetary authority that keeps promising an inflation it cannot deliver may at some point be jeopardized.

Additional readings:

[1] Understanding lowflation.

[2] A model of U.S. monetary policy before and after the great recession.